Far North Friday #60: Permafrost Fridge

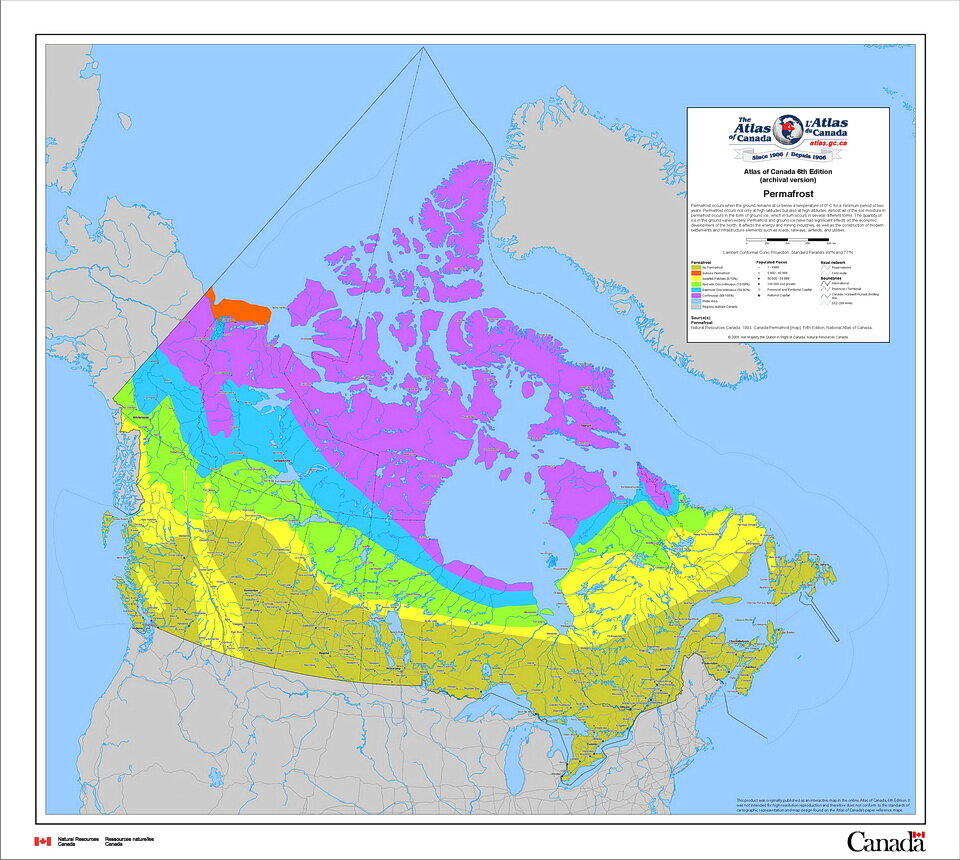

Permafrost is on my mind these days because I just finished a video on pingos in the Tuktoyakyuk area, Northwest Territories (https://youtu.be/tf5eugLSg_Q). Did you know that permafrost occurs in Ontario (Photo 1)?

Photo 1: Permafrost map of Canada, by Heginbottom, J.A., Dubreuil, M.A., Harker, P.A., 1995. Canada — permafrost, National Atlas of Canada, 5th edition. National Atlas Information Service, Natural Resources Canada, Ottawa. MCR 4177). The colour code: purple - continuous permafrost (90-100%); teal colour - extensive discontinuous permafrost (50-90%); light green colour - sporadic permafrost (10-50%); yellow - isolated permafrost (0-10%); olive green - no permafrost.

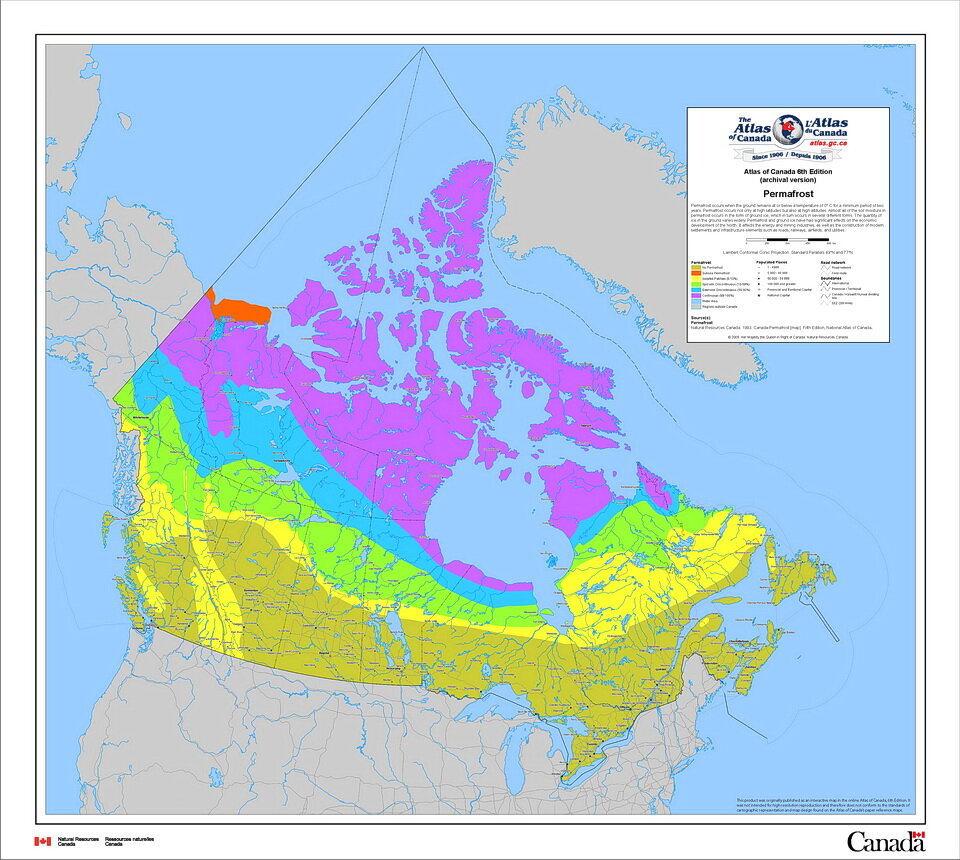

Did you know that permafrost can be used as a fridge? Early in my geological career, I was fortunate to work across northwestern Ontario, including areas that were underlain by discontinuous permafrost. What is permafrost? Permafrost is land that stays frozen (less than 0C or 32F) for two consecutive summers. In Ontario’s far north, the land close to the Hudson Bay is underlain by continuous permafrost (Photo 2).

Photo 2: A detail of the Ontario part of the permafrost map of Canada (Photo 1, above), by Heginbottom, J.A., Dubreuil, M.A., Harker, P.A., 1995. Canada — permafrost, National Atlas of Canada, 5th edition. National Atlas Information Service, Natural Resources Canada, Ottawa. MCR 4177). The colour code: purple - continuous permafrost (90-100%); teal colour - extensive discontinuous permafrost (50-90%); light green colour - sporadic permafrost (10-50%); yellow - isolated permafrost (0-10%); olive green - no permafrost.

Heading south from the Hudson Bay coast, that permafrost degrades into discontinuous permafrost patches. Permafrost disappears south of a line drawn from Moosonee to Sandy Lake (Image 2).

I recall vividly the first time I encountered permafrost. I was in a cedar swamp, using a hand-held auger, to collect soil samples. It felt like I hit a rock. When I looked at the sample in the auger, I saw ice crystals in the frozen sphagnum moss. Discontinuous permafrost? Maybe. Or perhaps late melting ground ice protected in the cedar swamp. Regardless, it was the highlight of the day. The water in those cedar swamp pools was really cold. And yes, I drank a lot of cedar swamp water that summer - and survived.

In those days, we did not have portable propane fridges. We kept our meat in Styrofoam coolers filled with ice (Photo 3).

Photo 3: Classic Styrofoam cooler that we used to cool our meat. We used to call these disposable coolers because they were so fragile, they barely lasted a week. We migrated quickly to those thick plastic coolers.

The commercial ice was flown in every 7-10 days on the food flight. The commercial ice that did not melt during the food flight was quickly packed into styrofoam coolers to cool our meat. We feasted for 2-4 days on fresh meat. After the 4th day, meals tended to be meatless, or was made from highly processed meat that even the bear would not eat, because the cooler ice had melted and meat was starting to go bad. When we discovered ground ice in the black spruce forest near the camp, we were elated. We pealed back the moss, dug a small pit, buried the meat in the ground ice, and covered the pit with the moss. Clever, you say? Well, not really. Many First Nation people used both ground ice and river ice to cool their food.

Most of the time the ground ice allowed us to keep meat for the 7-10 days between food flights. There was a downside. We discovered that black bears had fantastic noses capable of locating steaks buried in our ground freezer from 20 km away. It is amazing how persistent a black bear can be when anticipating a week’s supply of steak.

Bears did not discourage our use of the ground ice fridge. We kept flying in commercial ice for the Styrofoam coolers as back up, and to help keep the frozen meat frozen during the flight. We were happy to extend our meat meals for an entire week. We learned about black bear behaviour. And all of that came from a chance discovery of ground ice - perhaps discontinuous permafrost - in a cedar swamp in July.

Have A Question About This Note?

April 16/21 (Facebook April 16/21)